How did China achieve national unity during the Qing Dynasty?

A process of "natural cohesion" rather than result of imperialistic expansion

From the vantage point of China's historical evolution, however, the unification achieved during the Qing was not the result of a "conquest dynasty." It was underpinned by the enduring concept of Chinese identity.

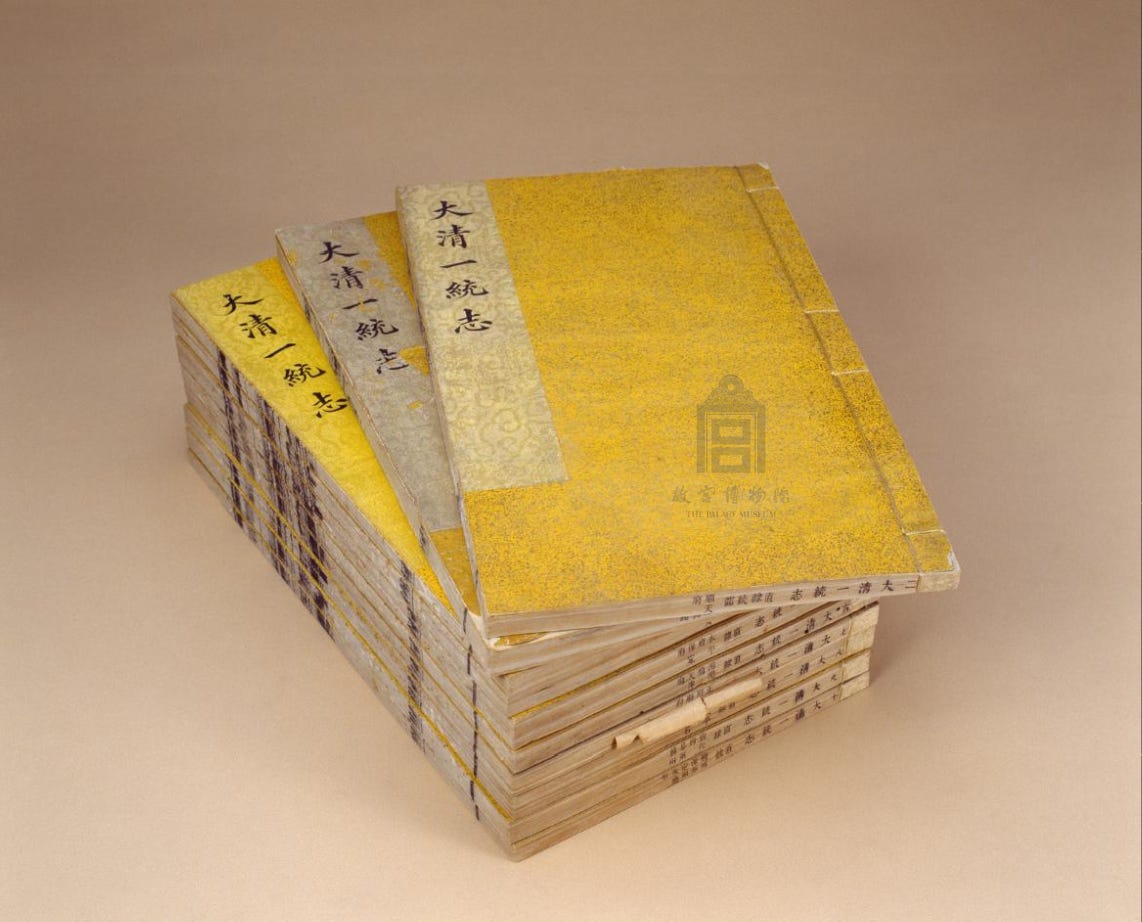

Since the crystallization of the concept of "great unity" in the pre-Qin era (before 221 BC), the establishment and evolution of a unified multi-ethnic state have been central to China's historical trajectory. Despite intermittent cycles of unification and fragmentation over more than two millennia following the Qin and Han dynasties (221 BC–AD 220), the ideal of a unified state has remained a consistent aspiration. The Qing Dynasty (1616–1911) stands out as a pivotal period in this journey, achieving a remarkable level of national unity. This accomplishment was driven not only by political necessity but also by economic integration and cultural synthesis.

National unity anchored in "Chinese Identity"

The Qing Dynasty unified China on an unprecedented scale and is regarded as the final traditional dynasty in Chinese history. Yet, its status within the broader historical narrative has been contested in various international and academic discourses. The "New Qing History" school, prominent in American scholarship, portrays the Qing as a regime rooted in "Manchu identity," framing its rule over "China" as a dominion over Han-people-majority regions rather than an extension of Chinese civilization. These interpretations implicitly challenge the continuity between the Qing and preceding Chinese dynasties, positioning it as an external conquest rather than a natural progression.

From the vantage point of China's historical evolution, however, the unification achieved during the Qing was not the result of a "conquest dynasty." It was underpinned by the enduring concept of Chinese identity. Although China's territorial unity was periodically disrupted, the integrative force of the "great unity" ideal consistently motivated fragmented regimes to strive for reunification. As the Qing transitioned from a regional regime to a national power, this Chinese identity played a defining role. The Qing rulers not only adopted the ideal of "great unity" but also redefined and expanded it to meet the demands of their era. In doing so, they validated their position within the continuum of Chinese dynasties while transcending the traditional Hua-Yi dichotomy (civilized vs. barbarian). This process laid a robust foundation for the subsequent development of the "Chinese nation" as a unifying concept.

For example, the Qing asserted its legitimacy by integrating itself into the genealogy of orthodox Chinese dynasties, affirming the historical roles of its predecessors and crafting a more inclusive lineage of legitimate rule. Furthermore, the Qing promoted ethnic integration across its vast territory by reframing the dichotomy between Hua and Yi into a shared identity of common subjection under imperial rule. This was further reinforced through the popularization of Confucian values, the cornerstone of traditional Chinese culture. The Qing rulers reinterpreted Confucian classics to construct a cohesive system of moral and cultural education, fostering a sense of collective identity that transcended ethnic boundaries.

By merging political strategy with cultural integration, the Qing Dynasty not only strengthened its own legitimacy but also ensured that the ideal of a unified Chinese state remained firmly embedded in the national consciousness.

National unification amid diverging Eastern and Western political trajectories

The unification achieved during the Qing Dynasty transcends the confines of Chinese history, holding profound significance within the broader context of world history, particularly against the backdrop of the 17th-century global crisis.

Geoffrey Parker, drawing on insights from the natural sciences, underscores that the Northern Hemisphere endured a "prolonged and severe global cooling event" during this period. This climatic upheaval coincided with a "series of revolutionary waves, and state collapses on a global scale." In Europe, the 17th century was marked by relentless turmoil, with only three years of complete peace recorded, as warfare became the predominant mechanism for resolving both domestic and international disputes.

China, too, was profoundly affected by the Little Ice Age during this era, grappling with devastating famines and widespread conflict amid the dynastic transition from Ming (1368–1644) to Qing. Yet, unlike the prolonged turbulence that characterized Europe, China's period of upheaval was relatively brief. Following their entry into the Central Plains, the Manchu regime systematically dismantled competing political factions through deliberate and strategic actions, ultimately achieving "great unity." This unification not only consolidated the Qing court's authority over an expanded territory but also established the geopolitical contours of modern China. From a European vantage point, the scope and scale of Qing unification might appear an almost insurmountable feat. However, within the framework of Chinese history, this accomplishment represents the continuation of an enduring historical mission—the relentless pursuit of national unification.

This divergence between China and Europe illuminates the contrasting responses of these civilizations to the monumental challenges posed by a global crisis. These divergent paths underscore two different trajectories of political civilization. Viewed through the lens of world history, Europe's fragmentation and China's unification embody two fundamental differences in political evolutions. The unification under the Qing Dynasty was not merely a testament to the resilience and adaptability of Chinese civilization but also a political pathway that stands in stark contrast to the Western model.

National unification beyond the nation-state paradigm

In the study of China's territorial history, several pivotal questions arise: How should the historical borders of China be defined? What intrinsic connections link the territories of successive dynasties? How did frontier regions become integrated into China's domain? These inquiries are central to understanding the enduring tradition of "great unity" in Chinese history.

Chinese academia has often struggled to provide robust explanatory frameworks for these issues, resulting in a lack of consensus regarding the Qing Dynasty's territorial unification. This gap in the scholarship has left space for the strong influence of the Western nation-state model.

Western scholarship, grounded in Europe's historical experience, frames the transformation from empire to nation-state as the definitive pathway to modern statehood. This perspective posits the disintegration of empires and the rise of nation-states as essential stages in state formation, attempting to universalize this trajectory.

However, the Western theory of nation-states—whether in terms of its historical underpinnings or developmental logic—fails to adequately capture the intricate processes underlying the formation of China's historical territories and its transition to modernity.

The Qing Dynasty exemplifies this divergence. Its territorial consolidation was not the result of imperialistic expansion but rather a process of "natural cohesion," building upon and refining the territorial legacies of preceding Chinese dynasties. Interpreting the Qing's territorial history through the lens of a "dynastic state-to-sovereign state" model aligns more closely with historical realities, offering a clearer understanding of how China evolved into a unified, multiethnic state and transitioned toward modernity.

Guided by the "great unity" ideal, the Qing Dynasty defined national boundaries and carefully integrated neighboring tribes and polities into the Chinese state. This approach fundamentally distinguished the Qing from colonial empires driven by aggressive territorial conquests. The 1689 Sino-Russian Treaty of Nerchinsk marked a significant transition, shifting from the traditional "borderless" conception of a dynastic state to a modern, "bounded" sovereign state. During the reigns of Emperors Yongzheng and Qianlong (1722–1796), efforts to delineate borders with neighboring vassal states further underscored the Qing's emerging modern sovereignty. This organic territorial evolution persisted until the Opium War I in 1840 when it was abruptly disrupted by Western colonial aggression.

The views don't necessarily reflect those of DeepChina.

The author is Zhu Hu, Dean and Professor at the School of History, Renmin University of China

This article is adapted from a speech delivered at the International Conference on Studies of the Community for the Chinese Nation during the Second World Conference of Sinologists.

Editor/ Liu Xian

Translator/ Li Minjie

Related articles

Chief Editor/ Yang Xinhua

Coordination Editor/ Liu Xian

Reviewer/ Liu Li

Copyeditor/ Zhang Weiwei

Image Editor/ Tan Yujie

About DeepChina

DeepChina is an elite academic initiative that offers objective and rational analyses on a broad spectrum of topics related to China, encompassing politics, economics, culture, human rights, diplomacy, and geopolitics.